Since the dawn of the 21st century, the boundaries of genetics have been pushed to the point where customising our DNA is no longer a fever dream or a product of mad science, it is a genuine reality. But is the prospect of gene editing really as positive as it seems?

Genomic alteration, commonly referred to as gene editing, is a process where the DNA sequence of an organism is changed by inserting, replacing, or deleting a part of it. At its core: “it allows scientists to modify the DNA of a living thing in order to produce a specific outcome or trait in that organism” according to Cambridge Cancer Researcher, Dr Ashley Nicholls. Classically, genetic mutations were observed as a product of radiation exposure that would allow scientists to witness the spontaneous alteration of genetic sequences. As technology evolved and new ideas emerged, the first targeted genomic changes were attempted on mice and yeast cells in the 1970s. However, this process, whilst remarkably precise, was crucially inefficient and, ultimately, stunted the flourishing developments in the field of genetics at the time.

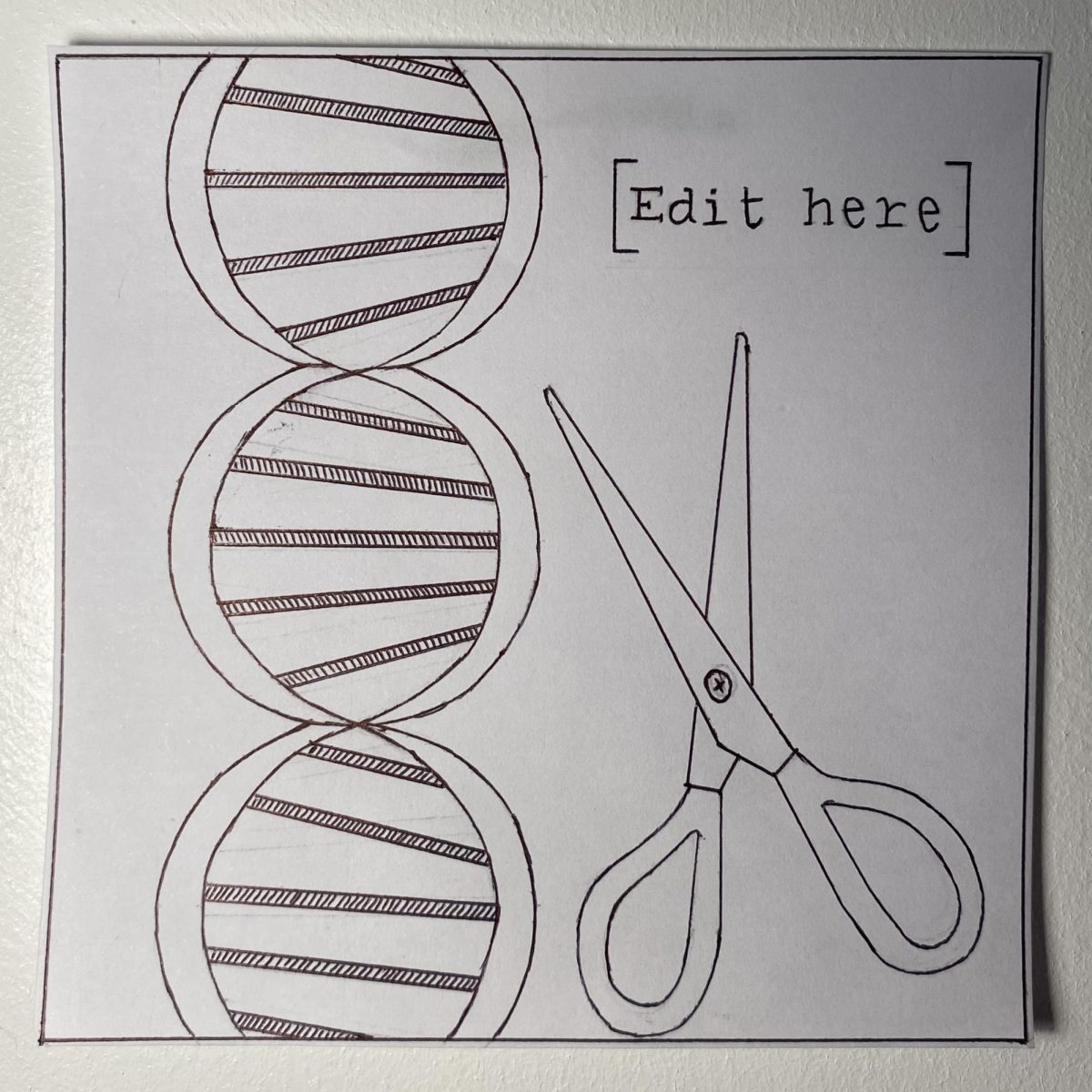

That was, until the invention of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology that suddenly opened the floodgates of genetic advancements. This technology could seemingly alter the coding of life in the space of mere weeks. CRISPR/Cas9 (invented by Nobel Prize winners Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier) is an accessible gene editing technology that makes it possible to correct errors in the genome and turn on or off genes in cells and organisms quickly, cheaply and with great ease. It is this simplicity that caused innovation and upheaval in the world of biochemical research.

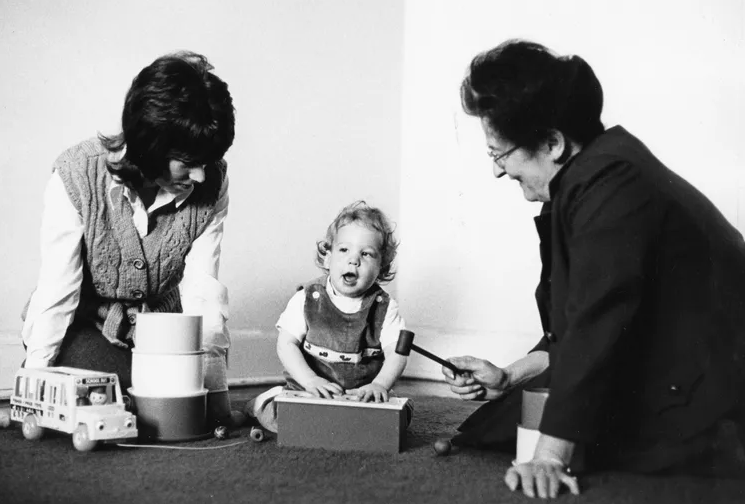

The uses of genomic editing are boundless as Jennifer Doudna herself expressed in an interview, when she stated how: “with CRISPR, you could imagine doing things with life that have never happened in nature but now are possible because we can alter the DNA at will. That is a profound thing.” Stretching from developing disease resistant crops, to eradicating invasive species, to curing genetic disorders, to even altering the physical appearance of organisms, the utility of genetic modification is undeniable. In fact, there have been cases of huge successes encompassing medicinal genetic alteration, such as the case of one-year-old Layla who underwent gene therapy to fight her Leukaemia. This was achieved by giving Layla genetically modified immune cells that provided her with a second shot at life.

However, where there is success there are bound to be limitations. The largest one being the infancy of this technology and the subsequent lack of knowledge surrounding the long-term effects of genomic modification. As a result, many scientists are incredibly cautious when analysing the future of gene editing as, crucially, no one knows what this future entails. Juliette Barrett from Manchester has first hand experience with the life-changing implications that genetic diseases can carry. Many of her family members have suffered greatly and unfortunately passed away due to the BRCA1 gene mutation that commonly results in breast and ovarian cancer. Prior to undergoing genetic screening, she received a great deal of cancer screening to ensure that she would not develop cancer in the meantime. She said: “I was offered precautionary measures of a prophylactic mastectomy and the removal of her ovaries. These came with terrifying psychological and physical consequences”. In a time where the technology and genetic engineering concept itself was still in its infancy, she expressed the hesitation, yet unwavering importance that accompanied her as she eventually underwent genetic screening to uncover whether she possessed this gene.

However now, as technology and scientific understanding have evolved, new possibilities and prospects have arisen. These include gene alteration that could take place before the baby’s birth. This could alleviate the mental and physical extremes of such mastectomies or any other substantial surgeries. These open up prospects where genes and ancestry are celebrated as opposed to damned. Prospects where parents can bear children free from the burden of genetic history. Ms Barrett said her ancestral genetics: “meant the difference between having children, and not”.

The future for genetic modification is bright, however, it is important to remember the daunting grey-area looming over the future of genomic editing. It is this unknown that worries scientist and ordinary people alike. We simply cannot see the generational impact of such practices. Have we pushed the boundaries of genetic advancements too far and too soon? Perhaps we will not know until it is too late.

Sidra • Oct 16, 2024 at 3:37 am

very educational and interesting

Lauren • Jan 25, 2024 at 9:47 am

A user friendly crash course in Gene Editing. I knew nothing about this before reading, but now feel I could at navigate my way through a conversation about it!

Kayleigh Brien • Jan 25, 2024 at 7:47 am

What a fantastic read!

Some excellent research has gone into this as we haven’t covered this in Biology – well done!

I am sure you will enjoy the genetic engineering booklet next year

Mick Crowe • Jan 25, 2024 at 6:34 am

Top work Dylan! You’ve done a great job of explaining a complex topic. The human interest sections bring it to life and make the implications clear.

Katy O'Brien • Jan 25, 2024 at 6:33 am

A really interesting and thought-provoking piece Dylan. It will be interesting to talk about this when we are studying “Frankenstein” next year!

Mrs Andrews (biology) • Jan 25, 2024 at 6:29 am

A well balanced presentation of the key points around CRISPR. Bravo!

Maia • Dec 13, 2023 at 6:56 am

Loved this. You’ve explained the scientific parts really well so it’s accessible and easily understood.

Jacqui Shirley - Organiser • Dec 7, 2023 at 7:50 am

A really interesting article with good mix of research and personal insight. I like that there are no easy answers