Society’s treatment of marginalised groups during epidemics can be just as damaging as epidemic themselves.

May 24, 2023

When it comes to epidemics, many people only view the damage that results as something physical. How many lives are lost? How have economies been affected. What if I told you that epidemics can also cause damage in a way that’s less tangible, but just as harmful? Society’s treatment of marginalised groups during outbreaks can be just as harmful as a epidemic itself. In the year ending March 2021, a little over a year since Covid-19 arrived in the UK, there were 124,091 hate crimes recorded by the police in England and Wales. So is there a correlation?

Well, I’m sure you’ve heard of the ‘Monkeypox’ outbreak that occurred in May 2022. Not many know that its name is misleading as rodents, not monkeys, are the source of the virus. And if you haven’t faced firsthand the way society treats you as a black individual, you might even miss it, or not realise that the use of the word ‘monkey’ plays into racist stereotypes about black and African people. There’s a long history of black people being referred to as monkeys, primarily from early American history. These stereotypes of an animal-like savage were used to rationalise the harsh treatment of slaves during slavery as well as the murder, torture and oppression of African Americans following the removal of slavery in America. Acts of racial violence were justified and encouraged through the emphasis on this stereotype of the ‘savage’.

But how does this stereotype affect our lives today? Many believe the dangerous myth that black people are far less sensitive to pain than white people. This untruth negatively impacts all black people, especially black women and their experience from healthcare authorities, particularly in childbirth. Even today, black women have the highest rates of mortality during childbirth than any other group. The report published by MBRRACE-UK in 2021, brought to light that Black women are 3.7 times more likely to die in childbirth than white women.

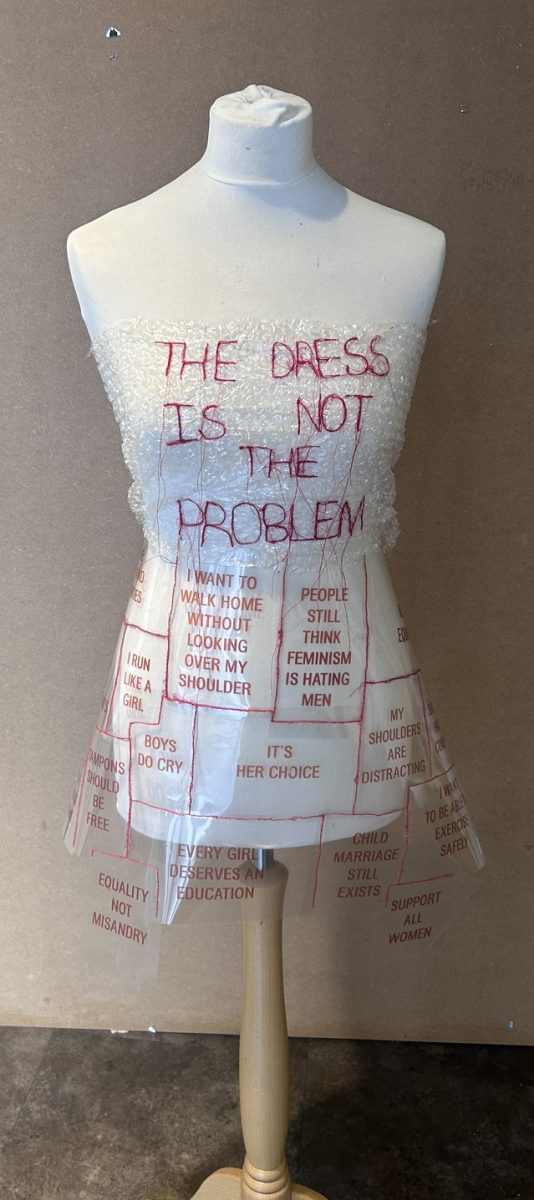

So stereotypes still affect the way groups are treated today by society. But not taking them as truth, especially in the wake of a new infectious disease being discovered, is the best way to combat them. However, the stock images used by media outlets in Europe and North America during the “Monkeypox” outbreak did the opposite. The majority of images used held those with dark skin and African complexions as examples for what the skin looked like when infected. It could be argued that as the images were from a previous outbreak in Nigeria in 2017, there isn’t an issue with how the press handled the initial outbreak. However, news outlets, despite reporting in countries with a white majority, didn’t use any other images to better represent the disease on different members of the population. The Foreign Press Association said this “perpet[ates]… this negative stereotype that assigns calamity to the African race and privilege or immunity to other races”. They also questioned; “Is the media in the business of “preserving white purity” through “black criminality or culpability”?” In other words, the belief that the African race / black people are destined for catastrophe and disaster whilst other races are immune to facing that in their lives.

It took months for “monkeypox”’s name to be changed; it was unclear if it would happen. On November 28 in 2022, the World Health Organisation officially changed it to Mpox. Even they confessed the disease’s original name played into “racist and stigmatizing language.” Though this was a positive adjustment, black and people of Asian descent weren’t the only ones affected by Mpox’s social affect; gay men were. Although Mpox spreads mainly through skin-to-skin contact, primary beliefs were that it was transmitted via sexual contact. This generated further stigma towards gay and bisexual men as they made up most cases in the beginning due to the limited knowledge of the disease at the time.

Yes, the outbreaks of Mpox and Covid-19 were so close together that many feared another lockdown, but that did not warrant treating people inhumanely. The treatment gay and bisexual men faced in the initial outbreak of Mpox mirrored the treatment the same minority group faced in 90s with HIV. “History doesn’t have to repeat itself with the stigma and monkeypox”, is an article by Ofole Mgbako, primary care HIV doctor, section chief of infectious disease at NYC Health. Here he described one of his patient’s experiences: “Those triaging him thought the rash might be monkeypox, so they rushed him into an isolation room where he sat, alone… No one came for hours. The doctor who finally entered the room was adorned in full personal protective gear — face shield, mask, gown, and gloves — and stood as far from the bed as possible, as if Ricky was somehow radioactive…”

However, anyone, regardless of their sexuality can catch the disease. But it was made clear in the initial 2022 outbreak when members of the Lgbtqia+ community made up a high percentage of the infected that governments weren’t moved to act, in contrast to how they did for Covid-19’s. The Mpox wave not only highlighted government disinterest of medical emergencies affecting marginalised groups, but how we need to change our approach to pandemics socially. Mpox cases were disproportionately higher among black, Hispanic, Latino men and non-binary people and not much was done to help for over a month. This isn’t right, all members of society should feel safe in the medical system and not fear mistreatment due to their identity. As Mgbako later said: “The stigma of a disease, especially new diseases, stages personal and systemic behaviours that allow infectious diseases to thrive…” And he is right, especially with the messaging around Mpox in the US, labelling it as a ‘gay disease’.

A way to tackle this as proposed by the Center of Disease Control is that; “Effective health communication about Mpox can help people make well-informed decisions to protect their health and the health of their communities, including getting recommended vaccines and practicing preventive behaviours”. In other words, if at every occurrence of disease, or even an outbreak of an old one, by describing it as “a legitimate public health issue that is relevant to all people”, and “us[ing] inclusive language, such as ‘us’ and ‘we’ pronouns”. By using non-inclusive phrases, it makes it easy for groups to be othered and sympathy to be disregarded in the mindset of ‘this won’t affect me, so I don’t care’.

There needs to be a better response and protocol, not just from health advisors when relating information, but in governments and news anchors to ensure the treatment we’ve seen during AIDs, and now in current times regarding Mpox and Covid-19, never happens again.

Kayleigh Brien • Jun 19, 2023 at 9:40 am

A really interesting read with some great research to support the points – very informative!

David • Jun 19, 2023 at 2:31 am

This is a well informed article that pushes the reader to think about words and their impact. It also highlights the impact words can have on minority groups and the stigma associated, a challenging and illuminating read.

Jacqui Shirley - Organiser • Jun 8, 2023 at 6:47 am

Such an intelligent and well researched article

helen • Jun 8, 2023 at 5:52 am

this was great, I thought the research for this article was very good it helped me understand the importance of the situation.