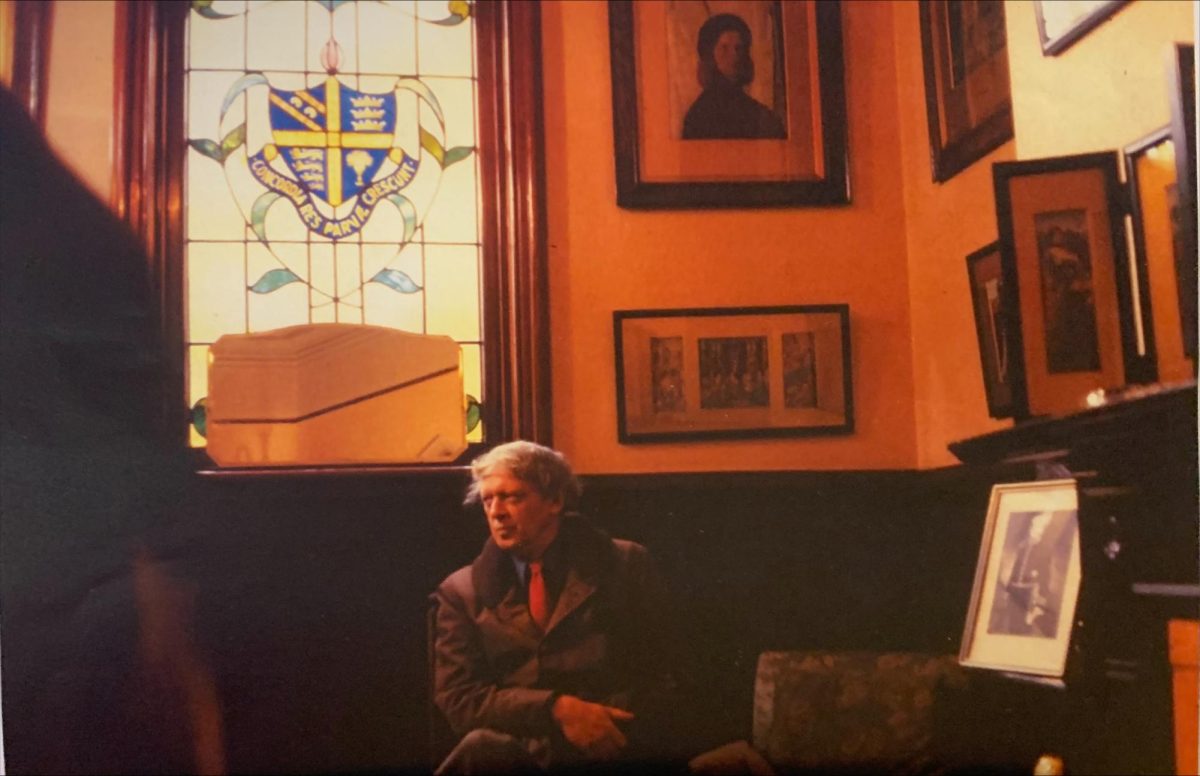

Born in 1917 in a quiet suburb north of Manchester city centre, Anthony Burgess is perhaps one of Xaverian college’s best known and most notorious alumni. His legendary 1962 novel, A Clockwork Orange, is unquestionably a landmark in modern surrealist and dystopian literature. Yet, over half a century later it remains as poignant and confusing as it was when first published.

Described by Burgess as: “a jeu d’esprit knocked off for money in three weeks,” the book is written in a dizzying form of futuristic teenage slang called Nadsat. Having spent time as a schoolmaster in colonial Malaya (now Malaysia) and Brunei, Burgess learnt the Malay language to a degree standard. His fascination with Russian literature took him to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) in 1961 where he learnt the basics of Russian and saw firsthand the elusive inspiration for Orwell’s 1984. With this linguistic fascination, Nadsat was born, combining Russian, Romany, and Cockney rhyming slang into a dystopian argot that I admit made reading this book a greater challenge than I first anticipated. Thankfully, the edition I read from came equipped with a glossary making translating this scintillating novel a much easier task.

However, the language this book uses is arguably not its most difficult aspect. The themes tackled by Burgess on the surface level are thoughtful and provocative; religion, government, crime, and punishment, before writing this novel Burgess had read Dostoevsky’s book of the same name. However, these can be hard to conceptualise while reading due to the narrator, Alex’s, incessant violence. Assault, robbery, sexual assault, even rape and murder are graphically described by Burgess as Alex and his gang of “Droogs” terrorise their city and its elderly inhabitants. Fuelled by milk sharpened by “knives”, the Nadsat for amphetamines, they unleash their brutality on most who cross them in a bloated display of extreme juvenile delinquency. The gang whip up cunning plans to gain access to people’s homes then attack and rob them or simply find someone on the street to beat with little motive.

This first half of this book is essentially a long streak of sporadic and methodical violence. In a letter written by Burgess he says of the first part, “I’ve just completed part one – which is just sheer crime. Now comes punishment.” It can feel confusing as to why you are reading such accounts with very little philosophical pay off but at times it can be difficult to look away. Reading such intense accounts would naturally disturb anyone, but the added layer of futuristic Anglo-Russian slang intensifies the distress this text causes as the amphetamines consumed by the characters surely intensifies their violent tendencies.

Despite the actions of our “humble narrator”, Burgess does present interesting ideas surrounding violence itself. While Alex’s actions are deplorable, it brings into question the idea of state sponsored violence and by what means it is necessary. After an unsuccessful attack, Alex is left near blind, and he is detained by police. Once at the police station, officers attempt to question him but when Alex refuses until a lawyer is present, he is beaten mercilessly, and they begin “bouncing [Alex] from one to the other like some very weary bloody ball”. While Alex is a mere teenage delinquent who has committed admittedly heinous acts, the police are no better than those who they are supposedly stopping. It seems illogical to fight fire with fire yet, the same primal lust for violence found in Alex, seems to be flowing through the Police.

At this point in the novel, something strange occurs. The reader begins to develop sympathy for the anti-hero.Once Alex is arrested, Burgess begins to explore the idea of criminal reform, part two – Punishment. The state attempts to brainwash him into a model citizen yet, their attempts do not bear fruit. However, despite this failed intervention, progress does occur in the concluding chapter. Instead of being made a model citizen by force and incarceration, Alex abandons violence by simply growing up. Once he turns 18, his past seems alien to him, no prison sentence needed.

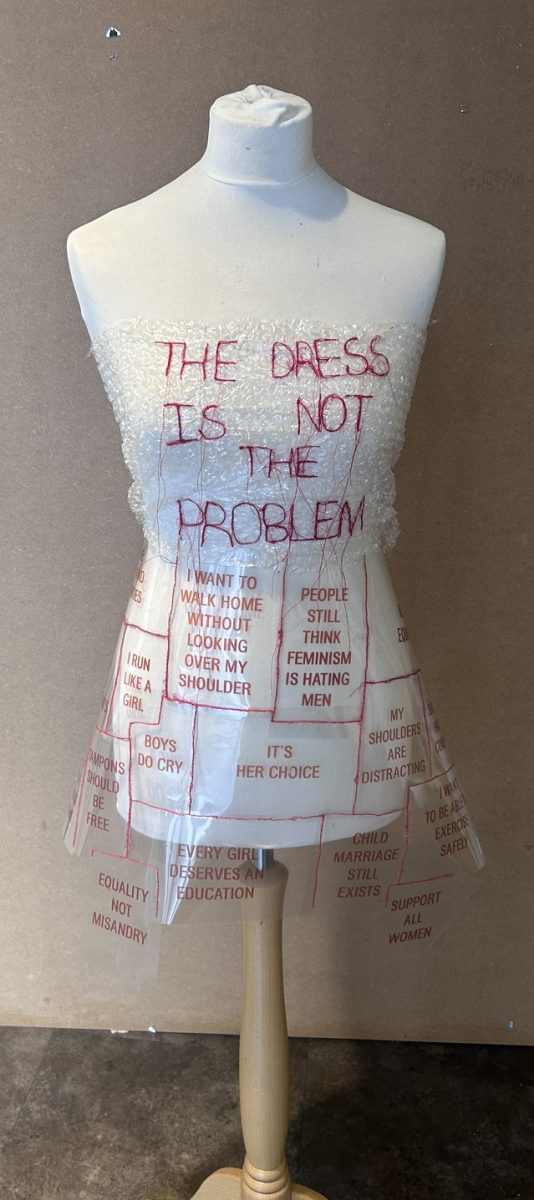

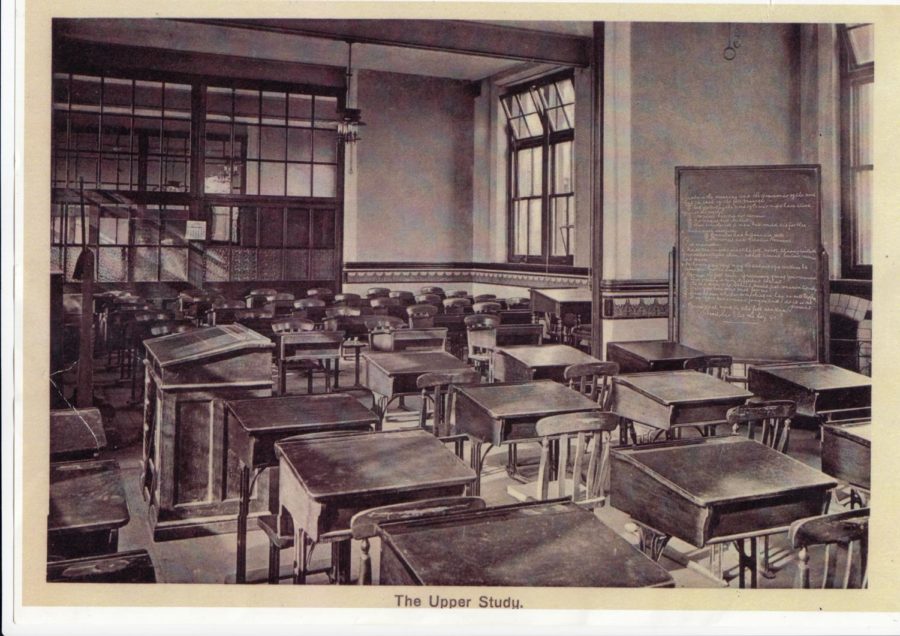

So, the big question is, to what extent are violence and youth linked? Is aimlessness and lack of purpose what dictates moral fibre in young people or is social deviation innate? These ideas may have borne fruit as a result of the Catholic ideals instilled in Burgess by 1920s Xaverian College. Although, contemporary students may have a more uplifting relationship with Christian teachings.

Part of his apparent fascination with teenage rebellion can been traced to Burgess’ time at the college where his history teacher at smuggled in a copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses which was banned in Britain, Ireland and the USA. This happened to be a cataclysmic event in his life an sparked a love for Joyce throughout his life. Censorship and the censorship of literature was a subject that Burgess felt strongly about especially after his emigration to Malta which saw 40 books of his own private collection destroyed by the Maltese postmaster general. This led to his impassioned lecture speaking out against this silencing from the post-war repressive state and his life-long fight against censorship can be seen with his writing about Salman Rushdie’s novel the Satanic Verses. His youth in a far more controlled, religious and especially Protestant version of England certainly shows his aversion to state control and the very existence of this novel is perhaps not solely about profound messages but testing the limits of literature.

This extreme imaginative elasticity is where Stanley Kubrick’s infamous film fails, because laying out the horrors of the book plainly for the viewer to see would never be enough to honour the weight of such terror left to brew in a human mind. Burgess spent much of his life answering for the decisions of Kubrick despite his lack of involvement in the film. Ultimately, this is a novel about violence and power, by what means is it necessary, who may wield it and how effective is it. The hypocrisy violence inspires puts state, church, and the public at odds with each other and our own human nature and perhaps having so much power held by so few people is the real crime. Between the style of narrative and its persistent presence, violence, seems personified as the true antagonist of this book. Whoever claims a monopoly on violence, claims societal power.

Burgess creates the perfect dystopia because much of it doesn’t lie solely in fiction. State brainwashing, and torture were very real in the Cold War era west, especially for “social deviants” such as Communists and LGBTQ+ people. The alienation felt between the youth and the old was a very real fact of the effervescent social cocktail that was the 1960s and that distance still exists today. A Clockwork Orange is a fully loaded, urban trawl that evokes the worst in humans and the states that we construct yet, its lack of heroes and idols engages a philosophy absent in most literature through time making this novel unquestionably timeless.

This book is a must read.

☆☆☆☆☆

This review would not have been possible without the help of the International Anthony Burgess Centre located right here in Manchester. I am especially grateful to Graham and Anna at the centre for their invaluable input and archival access. Their work online and at the centre has helped preserve the legacy of Anthony Burgess and his incredible body of work and you can visit them at:

www.anthonyburgess.org

Edie Watson • Dec 13, 2023 at 6:53 am

Amazing topic and very well written. Had me hooked the whole way through.

Jacqui Shirley - Organiser • Dec 5, 2023 at 8:38 am

A really well researched article making it a fascinating read