Last weekend I decided to watch 28 Days Later to remind myself of the plot before watching the highly anticipated sequel 28 Years Later. Turns out, I wasn’t the only one with this idea. The original has had a surge in popularity recently, and is currently the second most watched film on Letterboxd after 28 Years Later, whose trailer has become the second most watched horror trailer ever. But rewatching this film, I felt I had a new, different perspective to my first viewing.

28 Days Later is a revolutionary, genre-shaping zombie apocalyptic horror film, first released in 2002. With an initial budget of $8 million, the film grossed a stunning $84.6 million worldwide with the work of the director Danny Boyle, also known for 127 Hours, Trainspotting, and Slumdog Millionaire. This film was a huge success for the starring actor Cillian Murphy, as it paved the way for recent roles in Peaky Blinders and Oppenheimer. Other stars in the film include Naomi Harris (Moonlight); Christopher Eccleston (Doctor Who); and Brendan Gleeson (The Banshees of Inisherin). This was only the second film Alex Garland had written, leading to more successes including Never Let Me Go and Ex Machina.

For me, the film’s use of setting is one thing that makes it so compelling. If you have seen it, you’ll recall the iconic opening scene in which Jim (Murphy) awakens from a coma to discover London destroyed, while Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s ‘East Hastings’ fills the scene with a foreboding despair. There’s something so visceral and shocking about seeing such a famous city this way. When 28 Days Later was first released, I imagine the horror was the subversive impossibility of seeing London this way, but what stood out to me now was the familiarity of the derelict streets. Only several years ago many cities looked like this due to quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, it almost feels like a terrible ‘what if?’ from that uncertain time. The director, Boyle, even claimed: “what we used to think only belonged in movies feels more possible” now. When I watch 28 Years Later, I’ll be intrigued to see how this new perspective influences the filmmaking.

Making London appear completely deserted and desolate was no small feat. According to Murphy in an interview in GQ, they would shoot the film at “like four in the morning, just pre-dawn, and then … just as the dawn was breaking they would ask people to stop walking, and then the art department would run in and just dress it really, really quickly.” He also revealed that they utilised many cameras at all angles to acquire abundant footage.

But how revolutionary was 28 Days Later, really? If we look at zombie films before it, many portrayed slow, ambling undead zombies. Movies in this style such as Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978) could be equally chilling. Alternatively, 28 Days Later portrayed, not archetypal undead ‘zombies’, but victims of ‘the Rage virus’, still alive but infected with an insatiable violent instinct to kill. Boyle even chose to cast athletes as the infected to emphasise their power and agility. Although Boyle popularised the genre of ‘fast zombies’ he didn’t invent them. Nightmare City directed by Umberto Lenzi was the first to include faster moving zombies. Boyle’s choice is clearly influential in later horror inspired by this pioneering change such as The Walking Dead and Train to Busan.

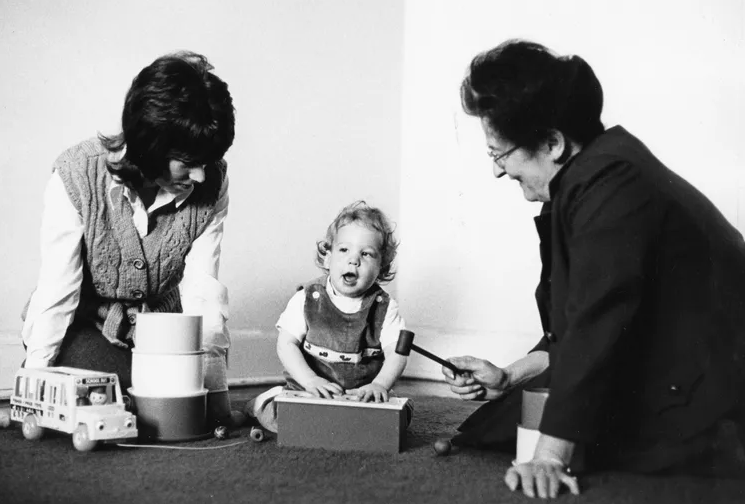

As an avid fan of the apocalyptic genre, I think the genre can often be boiled down into two key themes: hope for humanity, and monstrosity of humanity. In 28 Days Later we see survivors band together and bond through their trauma. Part of this message of hope comes from the destruction of the previous world, as there is no government, no institutions, no control, which could either result in a descent into chaos or an achievement of freedom. One scene that exemplified this for me was the characters’ observation of horses, free from their domestication and running wild together. Frank (Gleeson) remarks that they look: “like a family” and they’re: “doing just fine”, regarding them with respect. It is a poignant moment, perhaps to convey that nature would thrive without the constraints of humankind. Similarly, we saw this effect during the pandemic, as greenhouse gas emissions plummeted.

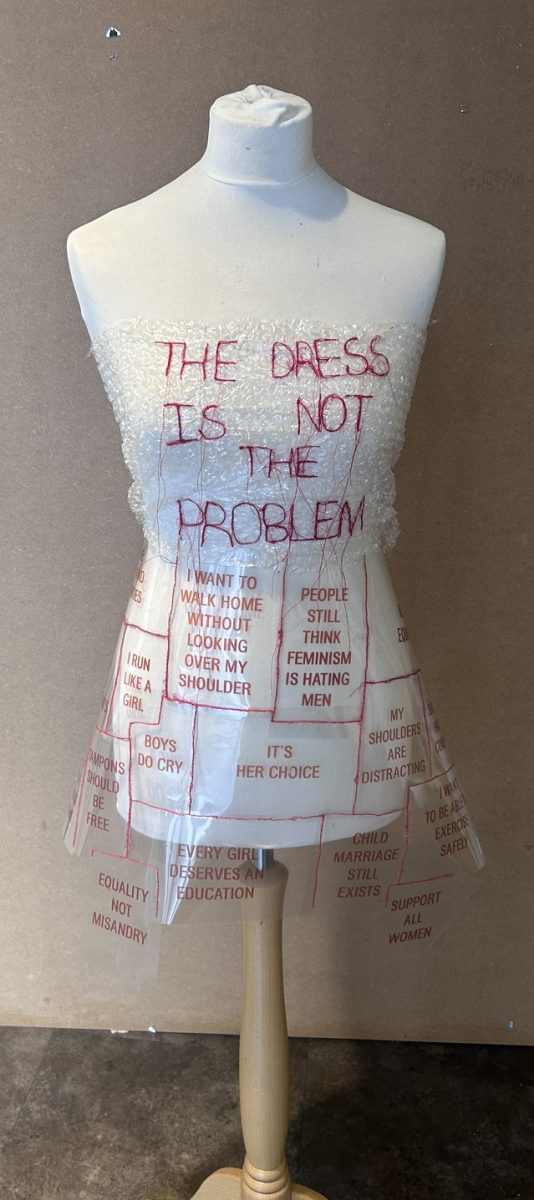

But on the flip side, the film carries a harrowing warning of what humanity may turn to without laws. Violence, especially sexual violence would be inevitable in the futile excuse to ‘repopulate’. But what makes this even more horrifying is the immediacy of this decision: this is only 28 days after law and order break down. This makes for one of the most sickening plot twists in horror history as we realise those who we thought were saviours had different intentions. Even the hero of the film can’t escape monstrosity, as demonstrated in one particularly gruesome, memorable scene.

In a post-pandemic world, films like 28 Days Later resonate more than ever. And the hordes swarming to local cinemas obviously agree.

28 Days Later can currently be streamed for free on BBC iPlayer or rented/purchased on Apple TV, Google Play Movies, or Amazon.