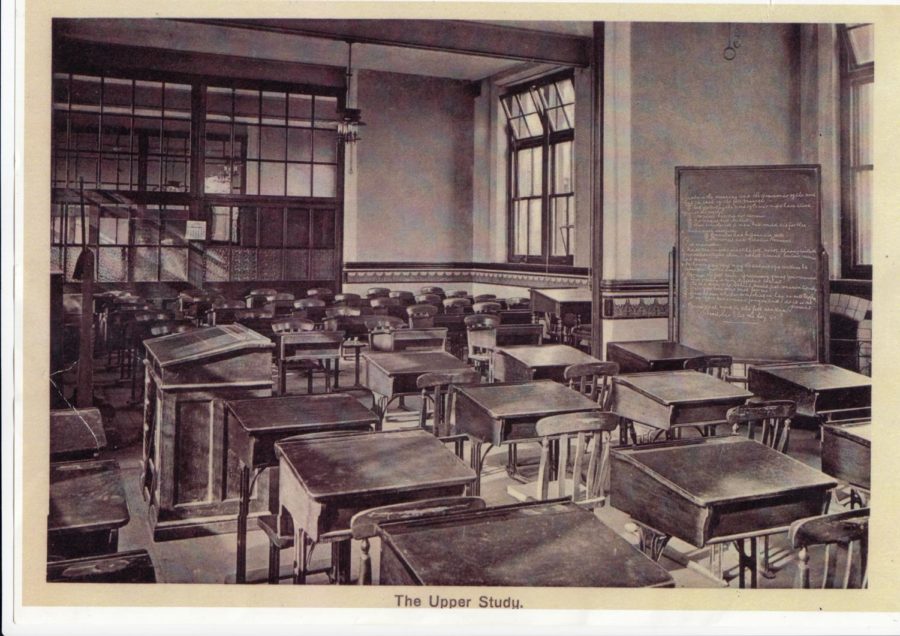

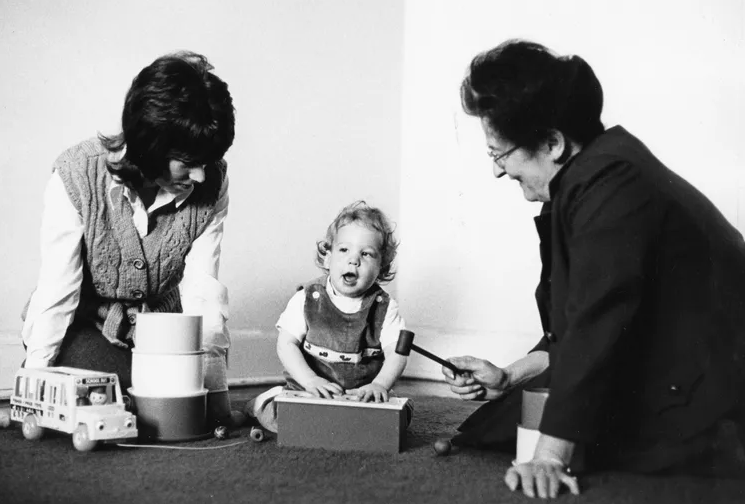

In 1969, American psychologist Mary Ainsworth conducted the ‘Strange Situation’ procedure. Young children were placed in an unfamiliar lab setting and experienced eight stages that put them into direct contact with varying combinations of adults. At the start, the child was alone with their mother. Then, a stranger joins them and subsequently the mother leaves. The stranger also leaves. The child is alone. Repeat.

Essentially, Ainsworth and her researchers wanted to know why children act the way they do. Are they born that way, or do the way that parents treat their children have a bigger influence?

This way of assessing infants is still used today when identifying a child’s attachment ‘type’. They are either secure (willing to be independent and explore but returning regularly to their mother), insecure (either extremely distressed at being alone or not at all bothered by it), or disorganised (showing all the different attachment types interchangeably).

At the time, this was a unique, revolutionary way of explaining the behaviour of young children and the parenting style of the mother.

But in 2025 I can’t help but wonder, how would this play out today?

The world of the late 60s is a far cry from the 21st century. We aren’t dealing with the political aftermath of the first cold war (for now), ‘Beatlemania’ is something our grandparents tell us about, we aren’t on the verge of a new millennium, and the children used in Ainsworth’s research are well into their 50s.

Despite the drastic differences from life then to life now, the Strange Situation isn’t uncommon in the world of Psychology, but researchers today would be assessing a new generation of child participants.

A compilation of studies put together by the BMC Psychiatry suggests that Ainsworth’s findings can be used to explain internet addiction in the modern world. They found that those on the insecure spectrum of attachment (from resistant to avoidant) are more likely to be addicted to social media than those who are securely attached.

I asked a group of Psychology students their opinions on Ainsworth’s research. 40% believed that the study is still relevant today, but the majority weren’t so sure. They told me that “parenting styles and tactics have changed since the study” and that it has become less relevant due to the “acknowledgement of other cultures” and the role they play in understanding attachment. For example, German children may be classed as having an insecure avoidant attachment in British or American culture due to the way German parents raise their families. In reality, these children have a perfectly healthy attachment.

Considering our changing perspectives on this research, when we discuss, debate and deconstruct the work of historical legends within this vast field, should the first question on everyone’s mind be – why are we still talking about this?

I don’t mean to be disrespectful or diminishing of the great impact and influence of Ainsworth’s research and the work of her teacher Bowlby, however influential work leads to scientific progress. Scientific progress leads to discoveries that disprove and build on the findings that we already have.

The concept of discovery in this context can be difficult to put into one single definition. If all approaches to psychology are theories, all with their own scientific merit, evidence and research attached, how can one approach – or one theory – be a singular explanation for the way we behave?

As a species we are evolving continuously. We are a cycle of thought, investigation, progress and discovery. With this more philosophical perspective in mind, a seed of doubt can grow. Can we rely on methods developed over 50 years ago to explain the complex actions of an infant born 50 days ago?

The way generations raise their children are so different from each other, perhaps changed forever by the invention of the internet and the rise of social media in the early 2000s. A 2022 Ofcom report found that most children acquire a phone from 9-11 years old, with a shocking 17% of 3-4 year olds given their first phone at this age. A phone is essentially a doorway unlocked to unlimited information, for better or worse. The way humans view each other becomes altered when we are (literally) viewing each other 24/7, constantly comparing, commenting, conversing.

A never-ending cycle of thought, investigation and comparison, rather than progress and discovery.

This interesting parallel between scientific evolution when it comes to the study of atoms, elements and chemicals and the evolution of the mind as a result of this may be more perpendicular than we realise. It seems that the smaller the device, the greater the technological advancement.

These advancements simply weren’t present in 1960s America and wouldn’t be for several decades. How much merit do old studies from this time really have? Can we ever truly rely on the thought processes of an era that is long behind us?

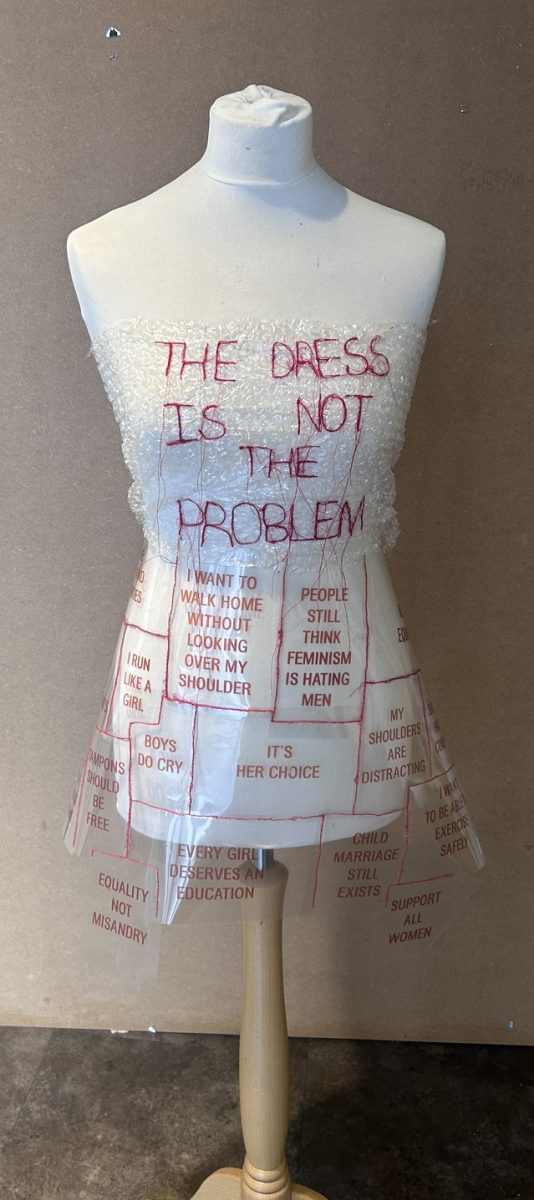

Society today has benefited enormously from the counterculture of this part of history. The introduction of the birth control pill, the civil rights movement, the growing feminist movement – even rock music – paved the way for the diverse and inclusive world we live in and strive to improve.

But Ainsworth (born in 1913) and Bowlby (born in 1907) came to their methods and conclusions in such a different time.

Ultimately, the debate over the value of ground breaking yet ageing research will never have a definitive answer. There is no singular time period in which we will always live in and therefore always compare with the decades that have come before. As long as we continue to build on these studies and develop our own, we will continue discover more about the complex workings of the human mind. Only then will we continue to learn.