We’ve all seen some form of crime in the media. But how accurate is the portrayal of crime, criminal, and victims in the TV dramas we watch, and the true crime podcasts we consume?

In 2017, Lavinia Woodward, an Oxford medical student, pleaded guilty for the stabbing of her boyfriend. She was able to avoid a prison sentence as Judge Ian Pringle QC said he believed the attack was “a complete one-off” and that prison would “prevent this extraordinary, able young lady from jail time that would ruin her career.”

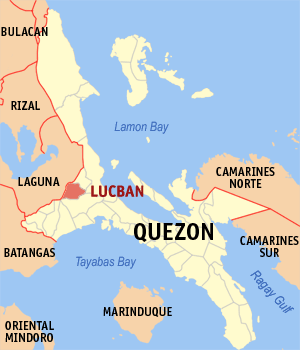

Angelo Kindundu, a police officer, states that the most common stereotypes that the media produces are: “Criminals being from low-income backgrounds, race, and gang related violence in certain areas.” This seems evident in the case of Lavinia Woodward, a white, wealthy, female Oxford student.

The media is also often accused of influencing crime by glamourising behaviour or inspires “copycat crimes” through extensive coverage: Heriberto Seda (also known as Eddie Seda) was reported as a copycat of the Zodiac Killer after the amount of coverage and glamourisation of the crimes and became an admirer. Eddie attempted to mimic the killer by choosing his victims based off their astrological sign and sent cryptic messages to the New York City Police in November 1989, following his idol in San Francisco in the 1960-70s.

The media can also influence the aftermath of a crime. In 2011, it emerged that newspapers had been hacking the phones of celebrities, politicians, and members of the public. Eventually, Rupert Murdoch decided to close the newspaper down after it emerged that Milly Dower, a teenager who was abducted and murdered, had her voicemails hacked, giving those who know her false hope.

Despite this, the media can prevent crime and bring justice. The Black Lives Matter movement started on social media gaining more that 44 million #BlackLivesMatter tweets from nearly 10 million distinct users on Twitter. Over half of these existing tweets that include these hashtags were posted from May to September 2020 after George Floyd’s death due to police brutality.

From 2014 to 2019, Travis Campbell (a PhD student in economics at the University of Massachusetts) tracked more than 1,600 Black Lives Matter protests across America, including more than 350,000 protesters. The main findings conclude there was a 15 to 20 percent reduction in lethal use of force used by police officers (roughly 300).

Kindundu states that social media is most effective at spreading crime stories quicker than other media sources. However, this could lead to misinformation. TV dramas and films tend to dramatise crimes such as “Dahmer”, exaggerating what truly happened. New outlets being the most informative source, may appear to show us facts and statistics. However, these stories can alter depending on the outlet’s political standings. An example being that right wing newspapers are more likely to showcase more street crime or focusing on the person’s race or religion despite it not being relevant.

Newspapers have been accused of fuelling crimes themselves. In Hopkins’ infamous column in The Sun, where she likened refugees to “cockroaches”, sparking a blistering response from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. The ECRI soon released its UK report, offering 23 recommendations for change, naming David Cameron and Nigel Farage as among the British politicians and institutions that were fuelling the rise of xenophobia in the UK. Police statistics also show a sharp rise in Islamophobia, antisemitic and xenophobic assaults. ECRI chair Christian Ahlund states that it is “no coincidence that racist violence is on the rise in the UK at the same time we see worrying examples of intolerance and hate speech in the newspapers, online and even among politicians.”

There are multiple cases of misinformation in the media, despite how harmful it can be, it can also unit us against the root of an issue to gain attention from the government after an unjust crime is committed.

Eliyah Foers • Jun 24, 2025 at 7:32 am

Very informative and researched

precious • Jun 23, 2025 at 7:39 am

This is really amazing!! It addresses issues that is destroying a lot…. well written and researched.

Aoife Geogheghan • Apr 2, 2025 at 6:35 am

This was a really insightful read that gave a balanced argument on an issue that is being increasingly overlooked. Very interesting and thought-provoking! 🙂

Emily Thompson • Apr 2, 2025 at 6:50 am

Wow! Super interesting topic! Thanks Emily

Ace Renshaw • Apr 2, 2025 at 6:32 am

Super interesting topic – really well researched!

Lisa • Mar 27, 2025 at 6:55 am

Very interesting and informative article. Thanks