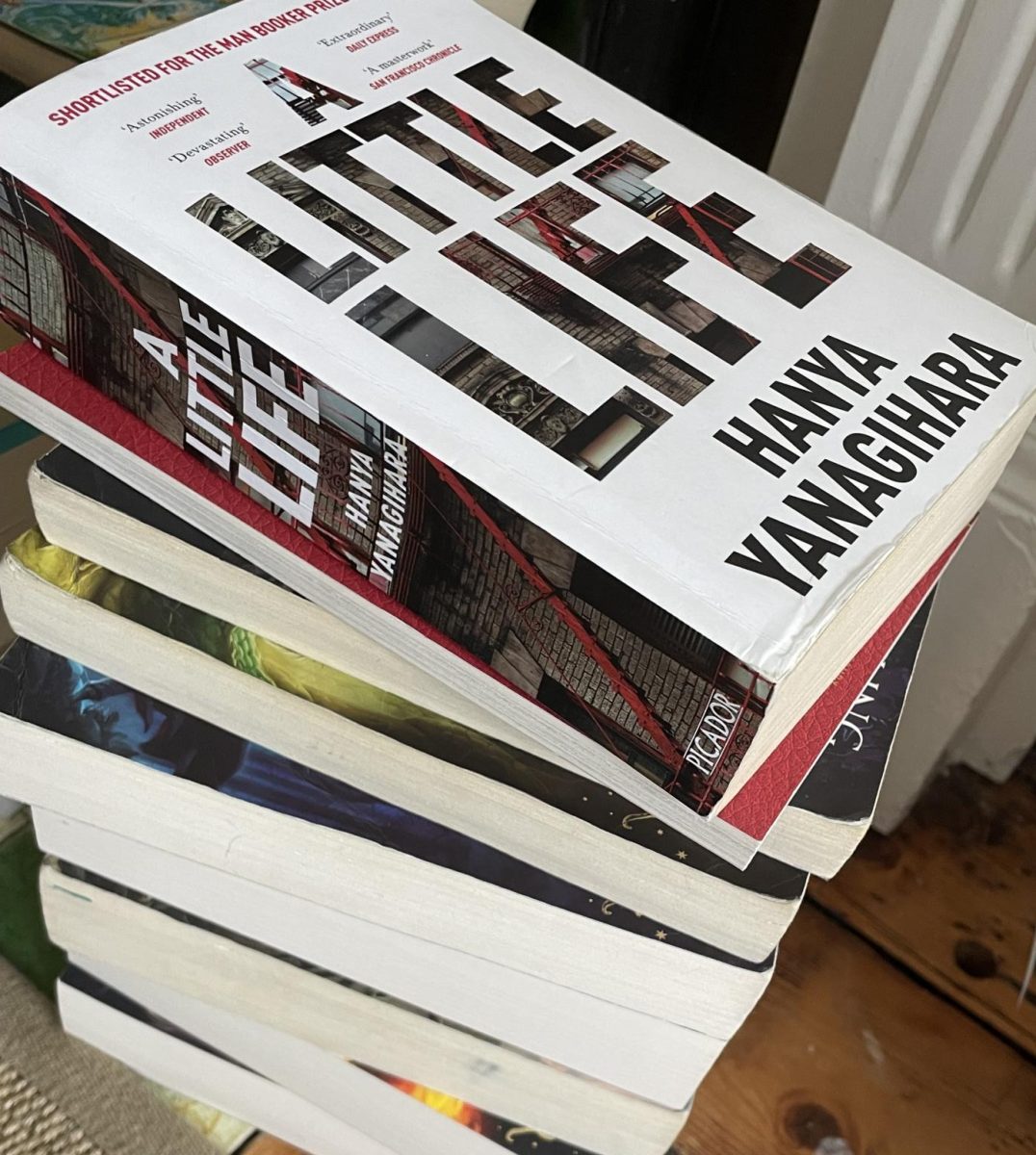

I must begin this review with a warning: This book is not one I can or will recommend ever in good conscience. If you are someone, like me, who values words, value the power they hold, then I must tell you to read this book with caution.

There is a laundry list of trigger warning to read before you buy this book. Please ensure you open this book at a time in which you are well, I strongly recommend reading another book alongside it, as a breather (I chose Percy Jackson). Something mindless and comforting to fall back to. This narrative addresses the following – Not just passing mentions but discussed at length and in great detail: child abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, violence, child prostitution, psychological manipulation, imprisonment, kidnapping, rape, self harm, suicide and suicidal ideation, grief, death, addiction, drug use, prejudice against disabled people.

When I was just shy of 100 pages in, I was sat in a hotel lobby in the middle of February reading and this lady walked in, saw the book, and stopped dead in her tracks. She said, “That is the best book I’ve ever read. But finish it when you have time to take care of yourself. It’s a tough one.” I said, “Oh it’s that bad, is it?” She said, “It’s that bad.”

It was futile to even attempt to distance myself from this book. It has firmly lodged itself under my skin and I’ll be picking it out from under my nails for years to come. It is not one that is easily forgotten.

Before reading I had heard of A Little Life’s reputation as being emotionally challenging. Like many people, it was the promise of this depth of feeling that drew me to it. I had seen hundreds of people on social media crying to this novel and thought any piece of media that can illicit such collective suffering must have something of note. I had to find out what all the fuss was about. This book is blisteringly and unapologetically raw and did indeed make me suffer.

Hanya Yanagihara deconstructs human relationships and explores this through her main cast: Jude, Willem, JB and Malcolm. Beginning in college, we see their friendship spans decades. We witness their jubilant triumphs, their bitter failures, their fallings out and makings up. We witness them in youth, in adolescence, in the shock of early adulthood, in the search for identity and hunger for success, with hopes and dreams and insecurities. We see them at the end of their life.

As the narrative progresses, Jude is singular and central. We see him in early childhood through interspersed memories of his past. It is within these insights to his past that we see an almost unbelievable depth of trauma. She created Jude as a character who we want to save. She raises the most difficult of questions: Is there such thing as an unsavable person? Is there a point in which someone cannot, will not, be saved, despite how many people love them?

My only criticism of the book is its excess. Everything seems to be inflated. The suffering and misery. Each of her characters achieve absurd success, stuff of childhood fantasies- in which Jude’s entire friend group are wealthy and renowned in their field.

In this sense, her writing seems to be removed from reality, a distorted scope of the American Dream, also seen in complete absence of discussion of social and political climate of the time. The narrative spans approximately 60 years, mostly based in New York and seems to be set in an everlasting modernity – the characters have phones and internet for majority of the novel and are entirely removed from changes of society around them. They are governed only by their interpersonal politics, the changing legalities of their relationships.

Hanya Yanagihara, in an interview with the Guardian in 2015, said: “I wanted everything to be turned up a little too high.” I think perhaps she fulfilled her objective a too well. This novel is a translation of misery. Read at your own risk.