As I write this, the death toll of Palestinians killed on the Gaza Strip has surpassed 34,000. On the 3rd of March 2024, First Minister of the North of Ireland Michelle O’Neill stated: “we are heartbroken for the suffering of the Palestinian people. I call for an immediate ceasefire.” From the first republican First Minister, this was a potent reminder of the connection between Ireland and Palestine, and the common oppression suffered by both nations at the hands of the ‘Great’ British Government.

On the 5th of March 1920, Winston Churchill deployed the Royal Irish Constabulary, more commonly known as the ‘Black and Tans’, into the North of Ireland to suppress the Irish rebellion. Acting on behalf of the British Government, the RIC was often comprised of ex-prisoners with minimal police training. The Black and Tans soon earned a reputation for capricious and indiscriminate viciousness against civilians.

In November 1920, the British Tans swarmed Tralee, seeking supposed retribution for the IRA abduction and killing of two RIC men. In addition to starving the area for a week, the Tans murdered three people. On the 14th of November, the RIC abducted and murdered a priest, Fr. Michael Griffin, in Galway, discarding his body in a bog in Barna. Finally, on the 11th of December, the recruits burned out the centre of Cork city. The Tans’ and the British Government’s intentions are perhaps best surmised by Lt. Colonel Gerald Smyth in his address to RIC recruits: “The more you shoot, the better I will like you, and I assure you no policeman will get into trouble for shooting any man.”

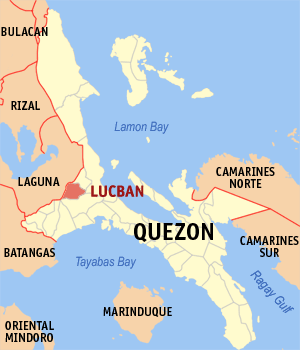

British incitement of violence was not limited, however, to maliciousness in Ireland. Following the defeat of the Ottomans on 30th of October 1918, Palestine came under British control. Acting as Secretary of State for the Colonies in November 1921, Churchill brought before the British Cabinet proposals for the recruitment of notorious Black and Tans for “a Palestine gendarmerie aggregating about 700 men”. This meant that 75-95% of the British gendarmerie comprised of the formerly disbanded recruits.

According to Douglas Duff, a former Black and Tan, four platoons of the British gendarmerie were assigned to Nazareth, where they forcibly took over the floor of a former Russian hospice for accommodations. When a Palestinian clerk resisted, the gendarmerie tossed his belongings and then him out of the second storey window. Duff later described an incident in Nablus, where one Gendarme proudly presented “an old cigarette-tin containing the brains of a man whose skull he had splintered with his riffle-butt”. The Black and Tans’ widespread murder of civilians is not dissimilar to the Israeli Government’s carpet-bombing of Gaza -both cower behind claims of justification to shirk criminal responsibility.

The British Government stretched the Black and Tans’ infamous sadism trans-continentally, setting the stage for generations of civil war. The legacy of British violence and systematic slaughter has left a gaping wound in the fabric of each respective society: it is no mystery why the Irish feel an affinity to the oppression of Palestinians. Sinn Fein’s continued fight for a united Ireland and an end to English sovereignty to has been compared to calls for an end to Israel’s occupation of Palestine.

In address to the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis in 2023, party President Mary Lou McDonald asked: “where is the protection of international law for every child killed in Gaza? For every Gazan mother holding the cold body of their dead child? Israel cannot be allowed to commit atrocities with impunity.” The bond between Ireland and Palestine is irrefutable.

Why is it that a nation must suffer violence in order to possess a sense of value for human life? Why must an individual first be a victim of oppression in order to exercise compassion for the oppressed? The connection between Ireland and Palestine is forged in the mutual loss of innocent life. Their solidarity serves as a reminder of the moral vacuum found in British history. Their shared history begs the important question: why do we call ourselves ‘Great’ at all?

Our Xavs Talks section will give students the opportunity to express their own personal opinions. These might be expressed with passion but we will still treat the issue with respect.

Jacqui Shirley - Organiser • May 9, 2024 at 9:40 am

A passionate personal opinion of a really relevant subject