Language is ever changing, ever evolving, due to several factors – including our social and cultural environment, emotion, the feedback of others and most critically in a modern context, the influence of the internet. As a child, I made up words for things I couldn’t name. In my household, cucumber was called “bookabar”, and our garden was known as the “dargen” for the first 3 years of my life. I’ve since outgrown this, but it is an interesting insight into how language changes.

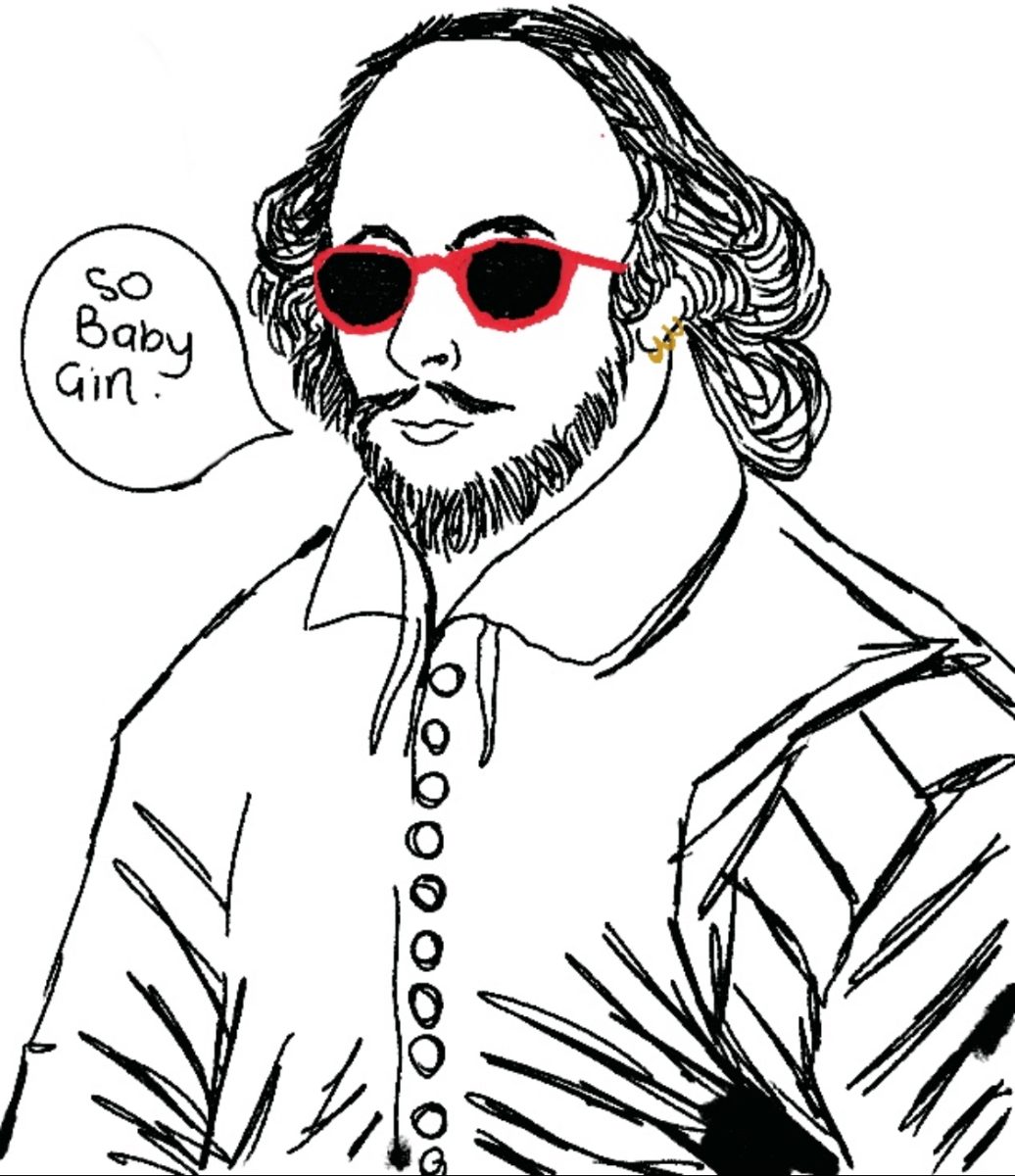

What is most baffling to me is how playwright William Shakespeare from the 17th century has had such a profound impact on our language, to such an extent that his terms are still frequently featured in our vocabulary four centuries on. According to the Shakespeare Trust, Shakespeare himself contributed approximately 1,700 words and expressions to the English language, my personal favourites include “Bandit” – Henry VI Part 2, 1594 and “Swagger” – Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1600. Shakespeare’s own idiolect in the 17th century was spread through poetry and performance as it still is today.

However, in the modern era, language is evolving at an even more accelerated pace. This is in part due to the impact of the internet – a catalyst in the ever-changing genealogy of English language. Seen most starkly in the sensationalised language on social media platforms like TikTok and Twitter. For example, the recently popular phrase, “gaslight, gatekeep, girlboss” a parody of the infamous, “live, laugh, love” has become a shared internet joke, in which we use to describe things that we, more specifically Gen Z, find defiant or distinguishable according to our admittedly distorted and morally questionable social criteria. I once saw a comment on a TikTok video of Barry Keoghan’s’ character in the thriller/comedy movie “Saltburn”, that said “He is the ultimate girl boss, gatekeep, gaslight”. This kind of satirical rhetoric casually used on social media has become a major influence on the language we use in our day to day lives.

While it is commonly thought that language employed on social media is segregated from language we use to engage in face-to-face conversation, it has become increasingly more featured in our immediate vernacular. A study of 2000 parents conducted by Samsung 86% of participants said they feel teens and young people spoke and entirely different language on social media.

The generational gap will only continue to expand. The Linguistic Society said, language will never stop changing. It is a brilliant product of societies through time, an ultimate construction and record of history and cultures. Dr Claire Childs, Professor of English Language and Linguistics at the University of York, commented on the impact of the internet on the development of language said: “When we see new language features appearing in social media, often these are already being used in conversation by particular social groups. Therefore, it is not necessarily the case that social media is causing new words to be invented, but that it can help these items to diffuse to new populations.”

The most recent example (and ongoing record of the evolution of language in recent years) is the Oxford Dictionary’s word of the year. The Oxford Press: “choose a winner that is judged to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year”. The chosen word for 2023 was social media slang term “rizz”. Considering that 2023 was a year we found ourselves amidst a genocide and the biggest humanitarian crisis in recent history, it was a difficult to reconcile this snapshot into history with the reality that it sorely failed to reflect. However, Dr Childs continues: “I would say that, overall, the role of the internet and social media in language change is often less than the general public might think. Nevertheless, social media can be a powerful influence in spreading new words/phrases or popularising old ones.”

Everyone has the ultimate goal of communicating effectively, most with care, all with the intent of being understood. It is therefore surprising that in a study conducted by The Economist, it was found that the average adult native English speaker who took their vocabulary test spoke within a range of 20,000 to 35,000 words. The Oxford English Dictionary estimates that there are around 170,000 words in current use, with an additional 47,000 outdated words. Meaning the scope of language for an average person is between 11.8% to 20.5% of vocabulary presently in use. Dr Childs concluded: “Research by Professor Peter Trudgill has indicated that face-to-face contact is important to spread innovative linguistic forms and/or to “level” distinctions between different accents/dialects, and social media does not involve this kind of face-to-face contact.”

While the internet has become a space where language is shared and changed, shock horror, social interaction with living breathing people is crucial to communication, therefore crushing our collective dreams of living like self-contained hermits. I apologise for the grief this may cause the introverts among us, me included. While language is changing and we mourn the necessity of socialisation, Leo will likely have found another model to chase after.

Jacqui Shirley - Organiser • May 9, 2024 at 9:03 am

A well researched article Plus I love your childhood made up words!